I am not a stranger to forest fires, having lived at various times in California, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming. My closest encounter was in Northern California, around 1993. I was camping in Hendy Woods State Park, with my young son and friends, in a borrowed pop-up camper. In the wee hours, the rangers woke us up and pointed down the hill at a fast-moving fire in the trees. Our camping site was the closest to the blaze so we had to pack up fast and turn the site over to firefighters. By the next day, everything was out.

The most recent encounter was with forest fire smoke. Last summer I traveled in my own popup camper for six weeks. The plan was to spend most of the time in the far northern parts of Montana. My route was based partially on the belief that the August temps would be cool up near the Canadian border. The temps were blistering hot and inside the camper thermometer sometimes topped 100 degrees. Furthermore, drought conditions led to an extreme number of wild fires in Oregon and Washington that year, and I was blanketed with a smoke haze most of the trip. I ended up changing my return route altogether.

Two years before that, I lived about 12 miles from the Arapahoe Fire, which burned a section of the Rockies, north of Cheyenne, WY. Before that, I watched the Colorado Fires (Waldo Canyon, Black Forest) on television as they burned areas where I had previously lived, camped, and hiked. Before that, while living in Colorado Springs, I lived through the Hayman Fire, the largest in Colorado history. The Hayman provided my first experience living in a city that is socked in with fire haze. By the time I was exposed to the Arapahoe Fire, I knew enough to stay indoors.

Two years before that, I lived about 12 miles from the Arapahoe Fire, which burned a section of the Rockies, north of Cheyenne, WY. Before that, I watched the Colorado Fires (Waldo Canyon, Black Forest) on television as they burned areas where I had previously lived, camped, and hiked. Before that, while living in Colorado Springs, I lived through the Hayman Fire, the largest in Colorado history. The Hayman provided my first experience living in a city that is socked in with fire haze. By the time I was exposed to the Arapahoe Fire, I knew enough to stay indoors.

Over the years I have driven or hiked through a hundred or more fire damaged areas including scorched acres in Yellowstone, the Black Hills, Central Colorado and the Laramie Range. As I pass in and out of National Parks and National Forest lands, I have seen countless fire danger warnings and Smokey the Bear signs encouraging me to Stop Forest Fires.

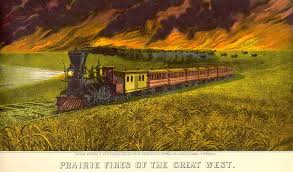

My experiences and Smokey the Bear taught me that wild fires equal forest fires. Right? Beaches don’t burn, deserts rarely burn. Only areas with lots of dry/dead/diseased trees, wind, and a spark are likely to experience wildfires. Wrong. I learned this past April that prairie lands and farmlands can burn too. In fact, in my new state of North Dakota, we are under a fire ban after one wildfire broke out near Bismarck. Rain is scarce and grasslands are dry. Haystacks, lined up in the fields like rows of used cars, can also burn. During harvest, the huge combines can heat up and start a fire in the dry grain fields.

My experiences and Smokey the Bear taught me that wild fires equal forest fires. Right? Beaches don’t burn, deserts rarely burn. Only areas with lots of dry/dead/diseased trees, wind, and a spark are likely to experience wildfires. Wrong. I learned this past April that prairie lands and farmlands can burn too. In fact, in my new state of North Dakota, we are under a fire ban after one wildfire broke out near Bismarck. Rain is scarce and grasslands are dry. Haystacks, lined up in the fields like rows of used cars, can also burn. During harvest, the huge combines can heat up and start a fire in the dry grain fields.

Prairie fires were disastrous for pioneers and a constant danger from spring through fall. Sometimes a farmer saw a red line on the horizon. The area was animated with sound as burning grass crackled, and the wind sweeping the fire onward made a roaring noise, still faint but unmistakably ominous. Shortly after seeing and hearing a distant prairie fire a settler would spring into action, making firebrands (burning wood) to set their own fires. Armed with hazel brush brooms to control their fires the pioneer, aided by his family, began burning strips of prairie around his fields in the hope of turning aside the flames. The inner edge of the flame was beaten out and the outer edge allowed to burn away.

I am used to fire bans in Wyoming and Colorado, but never expected to be “fireless” while camping up here. Hundreds of small lakes and ponds surround me where ever I go. Such a paradox – endless water holes surrounds by brittle grasslands ready to burn in an instant.

I learned from the National Forest Service (NFS), that prairie fires (like all others) are extremely important to the grassland ecosystem (providing it doesn’t take out your crop or baled hay). I learned this:

“Tallgrass prairie can accumulate an enormous amount of biomass (dead plants) in one year. The leaves die in the fall and the roots go dormant during the cold winter months. The following spring, new shoots grow. As years progress, the old dead leaf litter accumulates and creates a thick thatch covering the ground. New shoots find it harder to take in sunlight, while the ground stays cold and insulating causing a delay in the spring plant growth. Nutrients are locked up in plants yet to decay.”

“As litter accumulates prairie plants actually weaken and smother. Trees and woody bushes are able to invade stressed prairies. Trees create shade as they grow and cause even further restrictions in sunlight available to plants that need full sun. Fire is nature’s way of starting over. Fires are started naturally by lighting igniting flammable material or by man, both accidentally and intentionally. The Plains Indians started fires to attract game to new grasses. They sometimes referred to fire as the “Red Buffalo.” Ranchers today start fires to improve cattle forage and for prairie health.”

“The benefits of fire are enormous. The tied-up nutrients that take months or years to decay are within seconds turned to ash and in a form usable to plants. Sunlight warms the blackened ground and stimulates dormant plants to sprout and grow. Grazers are able to feed, uninhibited by dead litter, further stimulating growth. Trees and shrubs with the stems and branches exposed to the intense heat are killed, allowing the ground under them to receive full sunlight once again.”

So why the ban now? We don’t want too much to burn up and perhaps this is not the preferred time, based on farmer schedules. Planting season is probably not the best fire season.

Yesterday, however, the rain finally fell. I experienced the soft, soaking rain that brings joy to a farmer. Since irrigation is not a common practice here those who planted recently timed it just right. A friend called this rain the million dollar rain; had it not come farmers would be replanting by now and perhaps experiencing big loses.

Rain, drought, flood, wind, fire, tornados, earthquakes, freezing winters, oven-hot summers–somewhere life is difficult for someone at any given moment. Gratitude is always an option, even in the worst of the worst situations. Gratitude, and a willingness to open up to the circumstances and learn something new.

What would Abbie think?

S